Bolivia Can and Must Dollarize Now

It’s curious. I patiently watched the three-hour-and-35-minute debate organized by the Bolivian Academy of Economic Sciences among the economists representing the six main presidential candidates. Among other topics, they were specifically asked about their proposals on the exchange rate and, more precisely, their opinions on the “libertarian” proposal of dollarization. With the exception of one candidate, who confidently proposed a “fixed exchange rate with a floating band,” there seemed to be a consensus both in their proposals and in outright rejecting the dollarization of Bolivia’s economy. I must respectfully disagree.

Dollarizing Instead of Revaluing and Devaluing Again

All the economists, without exception, proposed a devaluation of the nominal exchange rate, which would only be relatively appropriate if accompanied by the prerequisite of a highly ambitious cut in structural public spending (not recurrent spending, as is often repeated ad nauseam) of at least 30% of GDP (subsidies for hydrocarbons and fuel imports alone account for about $5.5 billion, or 12% of GDP), securing as many dollars as possible through a sudden increase of up to $12 billion in external debt from multilateral organizations, and finally returning to a regime of mini-devaluations via the “bolsín” system. This is an excessively long, confusing, and dangerous path.

For starters, revaluing the boliviano means obtaining as many dollars as possible through debt, entrusting them again to the Central Bank of Bolivia (BCB), using them as backing to strengthen the boliviano, and “returning deposits to the people.” Even if this were desirable—which it isn’t—it would require an amount of time that the country neither has nor can afford to wait for. Moreover, in reality, there are no deposits to return because they have already been lost. Thus, the public would not be receiving anything back but would instead be handed resources from new debt, which they will eventually have to repay through taxes and inflation. Dollarization, on the other hand, can be immediate—implemented today or on the first day of a new government—and boils down to something as simple as the government recognizing the dollars already in people’s hands as the country’s official currency.

This translates into an immediate and far greater boost in public confidence compared to any alternative boliviano revaluation project. People would no longer have to bet on whether a new government will fall into the same vices of financing itself with legal reserves and the BCB’s reserves. Instead, they would place their trust in the commercial banks where they choose to deposit their money, with the guarantee that legal reserve requirements are eliminated and there is no obligation to entrust their deposits to the government in power.

The Myths of Dollarization

This wasn’t an argument raised by the candidates, but one of the most widespread myths about dollarization is that, under this regime, the national economy would shift from depending on national monetary policy to relying directly on the U.S. Federal Reserve’s monetary policy, thus giving up the ability to shield the economy from external shocks. However, Ecuador has experienced periods where inflation was not only lower than during times when it relied on its national central bank but even lower than in the U.S. The same has occurred in Panama, a dollarized economy without a central bank for over 100 years.

Another deeply rooted myth is that dollarization is proposed as a solution to all of the country’s problems, past and present. Critics argue that dollarization isn’t the solution because Panama, Ecuador, and El Salvador—where the latter two remain middle-income underdeveloped economies—still face high crime rates, political instability, and an endless list of issues. It’s unclear how they draw this conclusion, but while dollarization is not a sufficient condition for achieving higher levels of economic development, it is indispensable.

The final—and perhaps most widespread and dangerous—myth is that dollarizing an economy requires reserves, and if Bolivia lacks them, dollarization is impossible. This assumption is compounded by the notion—promoted by an economist who, despite fame, may lack basic knowledge on the subject—that the amount of dollar reserves needed would equal the value of the national GDP: $45 billion. Paradoxically, if the BCB had reserves, dollarization wouldn’t be necessary.

Of course, Bolivia does have dollars—plenty of them—otherwise, there would be no exchange rate at all. The only place where dollars are scarce is in the Central Bank and the broader banking and financial system.

Moreover, while dollars are indeed needed to dollarize an economy, the amount required is far less than what most conventional economists opposed to dollarization imagine. To dollarize, what truly needs to be replaced is the national currency in circulation (notes and coins), which typically accounts for only 5% to 15% of the M1 monetary aggregate, including demand deposits. All other components of the monetary base are dollarized in accounting terms.

Lessons from Dollarization in Ecuador: How Many Dollars Are Needed?

In 2000, President Jamil Mahuad decided to dollarize Ecuador’s economy at an exchange rate of 25,000 sucres per dollar, a decision heavily criticized at a time when annual inflation was 91%, with monthly peaks as high as 14.3%. Mahuad stated that the amount of sucres in circulation was equivalent to $436 million, and by the end of the exchange process, $425 million had been exchanged. In other words, the chosen exchange rate may have been appropriate, contrary to what Miguel Dávila Castillo, manager of Ecuador’s Central Bank (BCE) during dollarization, argued in 2017, claiming it should have been 32,411 sucres per dollar, though this depends on other factors like Purchasing Power Parity, a topic for another discussion.

Following Mahuad and Arízaga’s logic and extrapolating to Bolivia, at what exchange rate would the dollar need to rise to replace all boliviano currency in circulation with the BCB’s foreign exchange reserves? Based on the most recent data (December 2024), the notes and coins held by the public amounted to Bs. 71.55 billion, while the BCB’s foreign exchange reserves were $47 million. Dividing these figures, the exchange rate would be Bs. 1,522 per dollar.

However, since specific, up-to-date data on the monetary base is unavailable, the exchange rate needed to replace all boliviano currency in circulation with the BCB’s available reserves depends on the exact amount of currency in circulation, typically between 5% and 15% of the M1 monetary aggregate. With a reasonable estimate of Bs. 11.025 billion (10% of M1) in circulation and reserves of $47 million, the exchange rate would be approximately Bs. 235 per dollar.

The Myth of Available Reserves

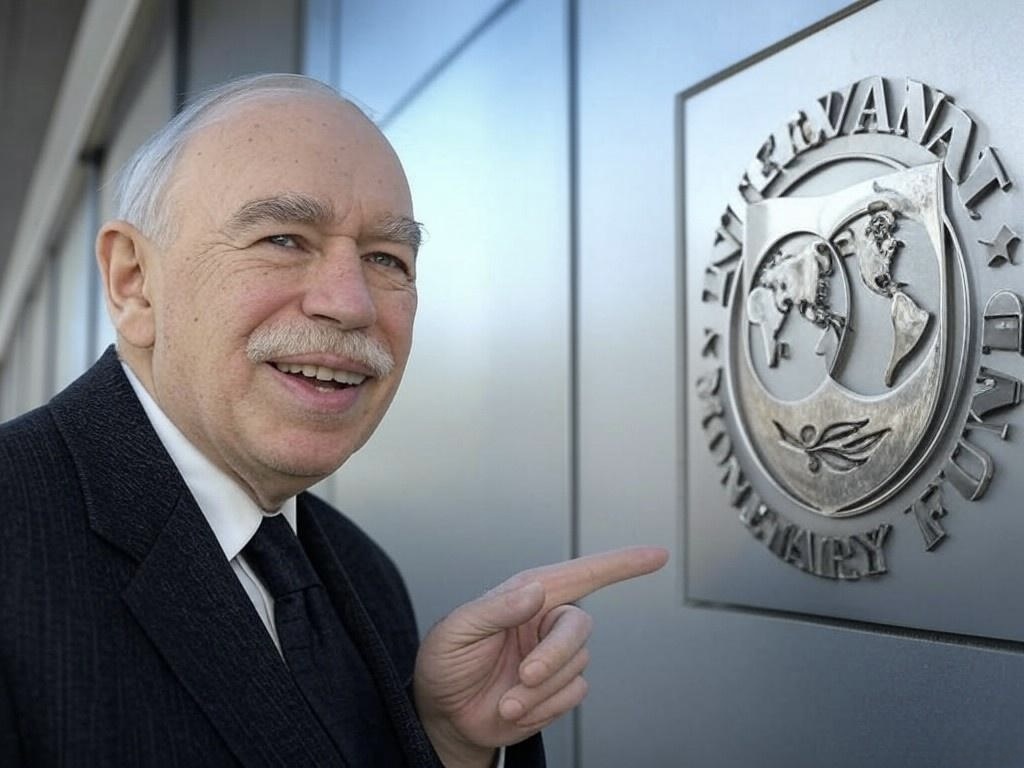

Let’s dig deeper. When President Mahuad noted that $425 million was exchanged by the end of Ecuador’s dollarization process, he wasn’t referring to the BCE’s available foreign exchange reserves, as they were actually negative. The money came from a rescue package provided by multilateral organizations, primarily the IMF, and largely from Ecuadorians themselves, who began depositing their dollars after the mere announcement of dollarization. In other words, the conditions for dollarizing Ecuador were even worse than those Bolivia faces today, with its 24% inflation rate (a 34-year high) if it were to pursue dollarization.

According to Alfredo Arízaga, Ecuador’s Finance Minister during dollarization, if part or all of the local currency is left in circulation as fractional currency, not a single dollar from the Central Bank’s reserves is needed to dollarize. Through a legal provision over a weekend, financial institutions can be ordered to convert all deposits and loans recorded in their balance sheets to a market exchange rate for that day, effectively replacing the national currency with the dollar.

More importantly, the value of money does not depend on its absolute quantity but on its purchasing power or ability to facilitate exchanges. Any amount of dollars is sufficient to dollarize an economy. If the money supply decreases, prices adjust downward to balance the amount of money with available goods and services. Pretending that the solution lies in accumulating massive reserves confuses the symptom (a lack of dollars) with the disease (the erosion of the boliviano and its loss of confidence).

Winners and Losers

Today, 25 years after its implementation, dollarization in Ecuador is more resilient than its detractors ever believed, enjoying over 95% public support and outlasting any trendy political regime or even any constitution.

Finally, a client once asked me, “With such impactful measures like dollarization, there’s always someone who wins and someone who loses—who loses?” The main losers are members of the banking and financial sector. By eliminating national monetary policy, dollarization also removes the moral hazard that has characterized systems like Bolivia’s “bolivianization” over the past 20 years. Banks and financial institutions would no longer be able to take excessive risks, confident that a lender of last resort would bail them out in a crisis using public funds to socialize losses. With dollarization, this safety net disappears. Banks can no longer rely on guaranteed financial lifelines, forcing them to act more prudently and limit their decisions to risks they can bear themselves, prioritizing the security of their depositors over the interests of their shareholders.

Originally published here on July 4th, 2025.